Lucie Duff Gordon

To Sir Alexander Duff Gordon, Tuesday, January 5, 1864.

We left Siout this afternoon. The captain had

announced that we should start at

While I was walking on the bank with M. and Mme. Mounier, a person came up and saluted them whose appearance puzzled me. Don’t

call me a Persian when I tell you it was an eccentric Bedawee young lady. She was

eighteen or twenty at most, dressed like a young man, but small and feminine and rather

pretty, except that one eye was blind. Her dress was handsome, and she had women’s

jewels, diamonds, etc., and a European watch and chain. Her manner was excellent, quite

ungenirt, and not the least impudent or swaggering,

and I was told—indeed, I could hear—that her language was beautiful, a thing much

esteemed among Arabs. She is a virgin and fond of travelling and of men’s society, being

very clever, so she has her dromedary and goes about quite alone. No one seemed

surprised, no one stared, and when I asked if it was proper, our captain was surprised. ‘Why not? if she does not wish to marry, she

can go alone; if she does, she can marry—what harm? She is a virgin and free.’ She went

to breakfast with the Mouniers on their boat

(Mme. M. is Egyptian born, and both speak Arabic perfectly), and the young lady had many

things to ask them, she said. She expressed her opinions pretty freely as far as I could

understand her. Mme. Mounier had heard of her

before, and said she was much respected and admired. M. Mounier had heard that she was a spy of the Pasha’s, but the

people on board the boat here say that the truth was that she went before Said Pasha herself to complain of some

tyrannical Moodir who ground and imprisoned the

fellaheen—a bold thing for a girl to do. To me she

seems, anyhow, far the most curious thing I have yet seen.

The weather is already much warmer, it is

Luckily we left all the fleas behind in the fore-cabin, for the benefit of the poor old Turk, who, I hear, suffers severely. The divans were all brand-new, and the fleas came in the cotton stuffing, for there are no live things of any sort in the rest of the boat.

Girgeh,

We have put in here for the night. To-day we took on board three convicts in chains, two bound for Fazogloo, one for calumny and perjury, and one for manslaughter. Hard labour for life in that climate will soon dispose of them. The third is a petty thief from Keneh who has been a year in chains in the Custom-house of Alexandria , and is now being taken back to be shown in his own place in his chains. The causes célèbres of this country would be curious reading; they do their crimes so differently to us. If I can get hold of anyone who can relate a few cases well, I’ll write them down. Omar has told me a few, but he may not know the details quite exactly.

I made further inquiries about the Bedawee lady, who is older than she looks, for she has travelled constantly for ten years. She is rich and much respected, and received in all the best houses, where she sits with the men all day and sleeps in the hareem. She has been in the interior of Africa and to Mecca, speaks Turkish, and M. Mounier says he found her extremely agreeable, full of interesting information about all the countries she had visited. As soon as I can talk I must try and find her out; she likes the company of Europeans.

Here is a contribution to folk-lore, new even to Lane I think. When the coffee-seller lights his stove in the morning, he makes two cups of coffee of the best and nicely sugared, and pours them out all over the stove, saying, ‘God bless or favour Sheykh Shadhilee and his descendants.’ The blessing on the saint who invented coffee of course I knew, and often utter, but the libation is new to me. You see the ancient religion crops up even through the severe faith of Islam. If I could describe all the details of an Arab, and still more of a Coptic, wedding, you would think I was relating the mysteries of Isis. At one house I saw the bride’s father looking pale and anxious, and Omar said, ‘I think he wants to hold his stomach with both hands till the women tell him if his daughter makes his face white.’ It was such a good phrase for the sinking at heart of anxiety. It certainly seems more reasonable that a woman’s misconduct should blacken her father’s face than her husband’s. There are a good many things about hareem here which I am barbarian enough to think extremely good and rational. An old Turk of Cairo, who had been in Europe, was talking to an Englishman a short time ago, who politely chaffed him about Mussulman license. The venerable Muslim replied, ‘Pray, how many women have you, who are quite young, seen (that is the Eastern phrase) in your whole life?’ The Englishman could not count—of course not. ‘Well, young man, I am old, and was married at twelve, and I have seen in all my life seven women; four are dead, and three are happy and comfortable in my house. Where are all yours?’ Hassaneyn Effendi heard the conversation, which passed in French, and was amused at the question.

I find that the criminal convicted of calumny accused, together with twenty-nine others not in custody, the Sheykh-el-Beled of his place of murdering his servant, and produced a basket full of bones as proof, but the Sheykh-el-Beled produced the living man, and his detractor gets hard labour for life. The proceeding is characteristic of the childish ruses of this country. I inquired whether the thief who was dragged in chains through the streets would be able to find work, and was told, ‘Oh, certainly; is he not a poor man? For the sake of God everyone will be ready to help him.’ An absolute uncertainty of justice naturally leads to this result. Our captain was quite shocked to hear that in my country we did not like to employ a returned convict.

Luxor,

We spent all the afternoon of Saturday at Keneh, where I dined with the English Consul, a worthy old Arab, who also invited our captain, and we all sat round his copper tray on the floor and ate with our fingers, the captain, who sat next me, picking out the best bits and feeding me and Sally with them. After dinner the French Consul, a Copt, one Jesus Buktor, sent to invite me to a fantasia at his house, where I found the Mouniers, the Moudir, and some other Turks, and a disagreeable Italian, who stared at me as if I had been young and pretty, and put Omar into a great fury. I was glad to see the dancing-girls, but I liked old Seyyid Achmet’s patriarchal ways much better than the tone of the Frenchified Copt. At first I thought the dancing queer and dull. One girl was very handsome, but cold and uninteresting; one who sang was also very pretty and engaging, and a dear little thing. But the dancing was contortions, more or less graceful, very wonderful as gymnastic feats, and no more. But the captain called out to one Latifeh, an ugly, clumsy-looking wench, to show the Sitt what she could do. And then it was revealed to me. The ugly girl started on her feet and became the ‘serpent of old Nile,’—the head, shoulders and arms eagerly bent forward, waist in, and haunches advanced on the bent knees—the posture of a cobra about to spring. I could not call it voluptuous any more than Racine’s Phèdre. It is Venus toute entière à sa proie attachée, and to me seemed tragic. It is far more realistic than the ‘fandango,’ and far less coquettish, because the thing represented is au grande sérieux, not travestied, gazé, or played with; and like all such things, the Arab men don’t think it the least improper. Of course the girls don’t commit any indecorums before European women, except the dance itself. Seyyid Achmet would have given me a fantasia, but he feared I might have men with me, and he had had a great annoyance with two Englishmen who wanted to make the girls dance naked, which they objected to, and he had to turn them out of his house after hospitably entertaining them.

Our procession home to the boat was very droll. Mme. Mounier could not ride an Arab saddle, so I lent her mine and enfourché’d my donkey, and away we went with men running with

‘meshhaals’ (fire-baskets on long poles) and

lanterns, and the captain shouting out ‘Full speed!’ and such English phrases all the

way—like a regular old salt as he is. We got here last night, and this morning Mustapha Agha and the Nazir came down to conduct me up to my palace. I have such a big rambling

house all over the top of the temple of Khem. How I wish I had you and the chicks to

fill it! We had about twenty fellahs to clean the dust

of three years’ accumulation, and my room looks quite

handsome with carpets and a divan. Mustapha’s little

girl found her way here when she heard I was come, and it seemed quite pleasant to have

her playing on the carpet with a dolly and some sugar-plums, and making a feast for

dolly on a saucer, arranging the sugar-plums Arab fashion. She was monstrously pleased

with Rainie’s picture and kissed it. Such a

quiet, nice little brown tot, and curiously like Rainie and walnut-juice.

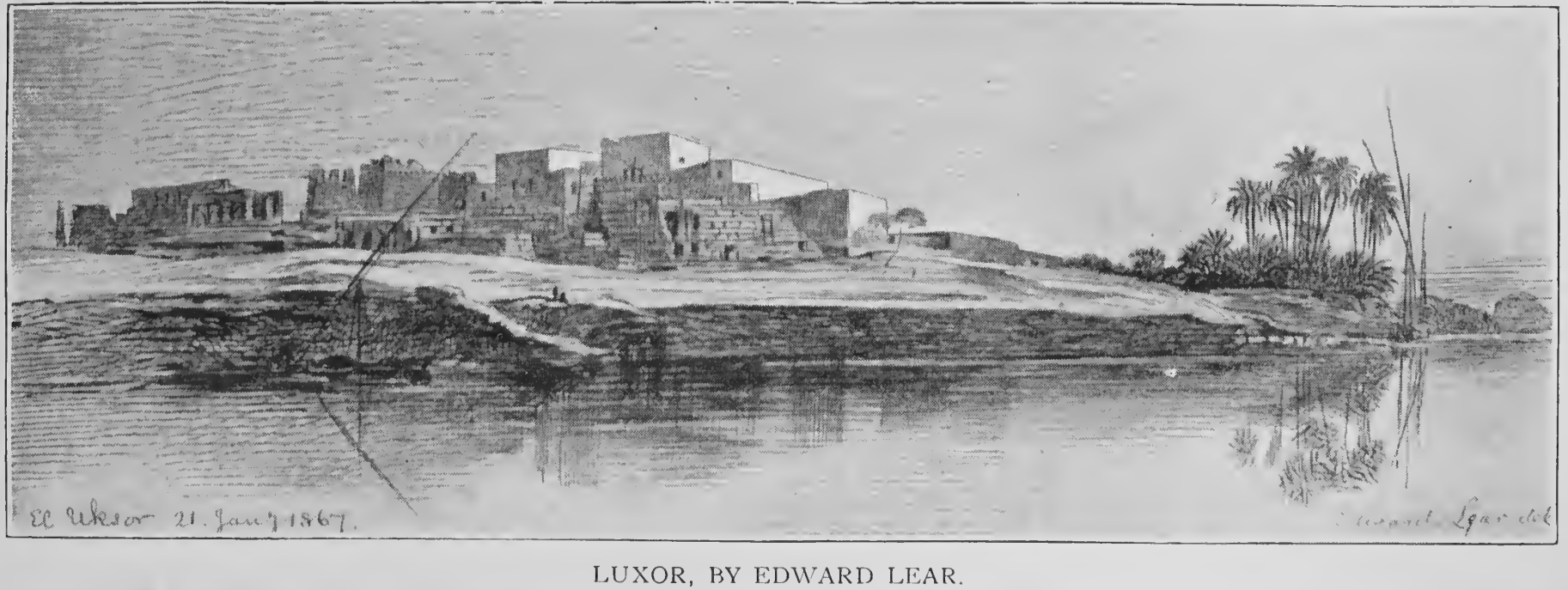

Luxor, by Edward Lear, showing Lady Duff Gordon’s house, now destroyed

Luxor, by Edward Lear, showing Lady Duff Gordon’s house, now destroyed

The view all round my house is magnificent on every side, over the Nile in front facing north-west, and over a splendid range of green and distant orange buff hills to the south-east, where I have a spacious covered terrace. It is rough and dusty to the extreme, but will be very pleasant. Mustapha came in just now to offer me the loan of a horse, and to ask me to go to the mosque in a few nights to see the illumination in honour of a great Sheykh, a son of Sidi Hosseyn or Hassan. I asked whether my presence might not offend any Muslimeen, and he would not hear of such a thing. The sun set while he was here, and he asked if I objected to his praying in my presence, and went through his four rekahs very comfortably on my carpet. My next-door neighbour (across the courtyard all filled with antiquities) is a nice little Copt who looks like an antique statue himself. I shall voisiner with his family. He sent me coffee as soon as I arrived, and came to help. I am invited to El-Moutaneh, a few hours up the river, to visit the Mouniers, and to Keneh to visit Seyyid Achmet, and also the head of the merchants there who settled the price of a carpet for me in the bazaar, and seemed to like me. He was just one of those handsome, high-bred, elderly merchants with whom a story always begins in the Arabian Nights. When I can talk I will go and see a real Arab hareem. A very nice English couple, a man and his wife, gave me breakfast in their boat, and turned out to be business connections of Ross’s, of the name of Arrowsmith; they were going to Assouan, and I shall see them on their way back. I asked Mustapha about the Arab young lady, and he spoke very highly of her, and is to let me know if she comes here and to offer hospitality from me: he did not know her name—she is called ‘el Hággeh’ (the Pilgrimess).

I have been ‘sapping’ at the Alif Bey (A B C)